Seen, Heard, Esteemed: Living History Narratives of Georgetown County, SC, showcases Gullah Geechee changemakers from this region in their own words. These narratives range from the Civil War to today, and while they hail from different perspectives and times, they each show the vital role African Americans and enslaved Africans played in the history of this region.

Our narratives are based on research and archival documents; however, some aspects of these stories have been fictionalized to fill in gaps in the historical record.

To view and listen to this content on the Brookgreen App, download from the Apple App Store or Google Play Store

Credits

Voice Actors: Lauren Bassard, Jordan Taylor, Willow James, Veronica Gerald, Robert Laws, Carson Hebblethwaite, Liam Mulshine. Audio Engineers: Mckinley Devilbiss, Timothee Khayat Researchers/Writers: Jayson Hicks, Dalton Carlson, Catie Zimmer Designer: Kaylie Van Sistene

This project is a collaboration between Brookgreen Gardens, The Charles Joyner Institute for Gullah and African Diaspora Studies, and the Athenaeum Press at Coastal Carolina University, and has been partially funded by a generous grant from South Carolina Humanities, the Gaylord and Dorothy Donnelley Foundation and the National Archives.

Abraham Herriott

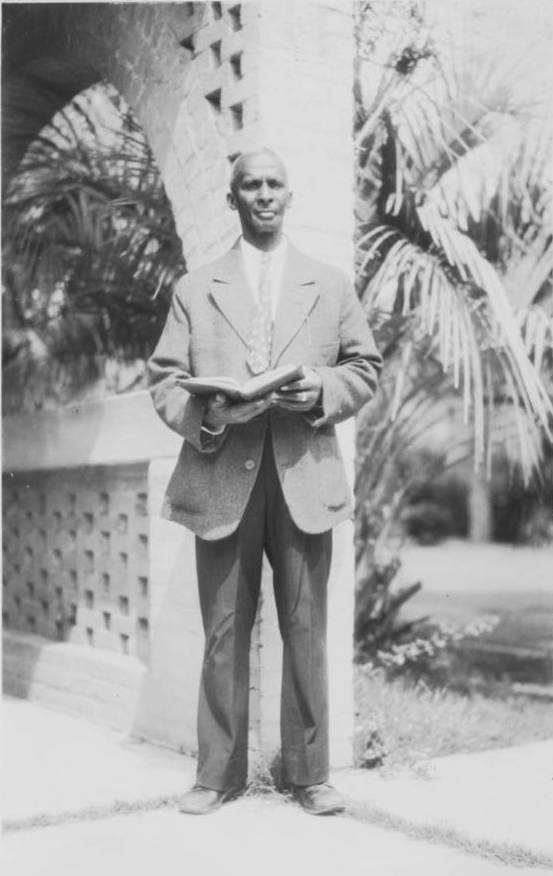

Abraham Herriott, 1930s, Brookgreen Gardens Collection

Abraham Herriott was born in 1874 on Sandy Island, a historic freedman community just across the Waccamaw River from where you are standing. Sandy Island is only accessible by boat. In fact, the dock near the Lowcountry Center used to be where the island’s residents landed.

Because many of the African American residents owned land on Sandy Island, they represented a large voting block for the region. This community unanimously voted for John Bolts in 1898 and 1900. When the Huntingtons bought the plantations that now make up Brookgreen, Herriott served as a land manager and conduit for the Huntington's to the Sandy Island community, focusing their philanthropic resources on his home--from building the Sandy Island School to helping preserve the rice fields.

Abraham Herriott, a community leader on Sandy Island, corresponded regularly with Archer and Anna Hyatt Huntington, the founders of Brookgreen Gardens, between 1930 and his death in 1957. These are selections of his letters as preserved in the reports of Brookgreen manager, Frank Tarbox, in the Brookgreen Gardens Archives.

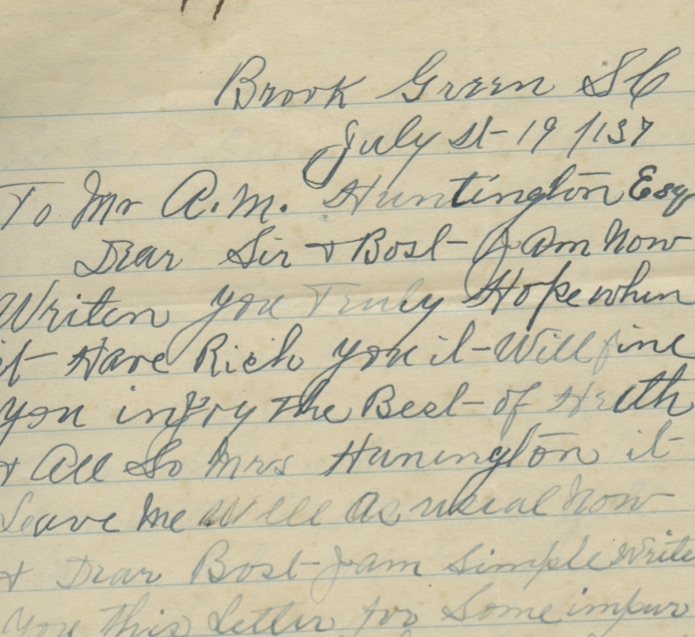

Photo: Letter from Abraham Herriot, 1936, Brookgreen Gardens Archives

In local papers, Abraham Herriott was proclaimed the “Rice Czar” of Sandy Island. Herriot oversaw the harvesting of rice well into the 1950s, long after most of South Carolina. During the 1930s, Archer Huntington commissioned a photographer to capture the quickly disappearing rice culture, including the photograph you see here.

Photo: Abraham Herriott Winnowing Rice, 1930s, photographed by Bayard Wooten, Brookgreen Gardens Collection.

Civil War

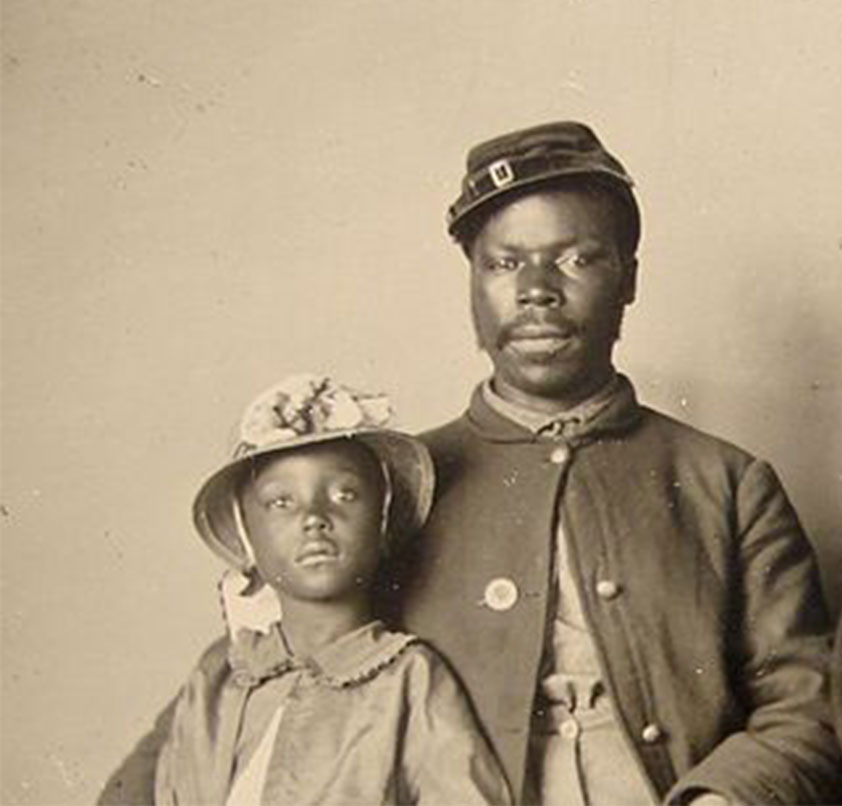

Almost a thousand enslaved African Americans from the Waccamaw Neck and Georgetown enlisted in the Union Army, joining nearly 200,000 Black men in service during the Civil War. These fictionalized narratives are based on written testimonies given by these soldiers of their experiences after enlisting in Georgetown and being assigned to Beaufort, South Carolina.

Almost a thousand enslaved African Americans from the Waccamaw Neck and Georgetown enlisted in the Union Army, joining nearly 200,000 Black men in service during the Civil War. These fictionalized narratives are based on written testimonies given by these soldiers of their experiences after enlisting in Georgetown and being assigned to Beaufort, South Carolina.

Caption: A group of “contrabrands,” 1865, Library of Congress.

While these new Black soldiers were adjusting to life as freemen, they had very little resources. The Civil War disrupted all sorts of food supplies, so often meals consisted of rationed salt horse or salted horse meat that preserved well. Although far from being ideal, these Black soldiers relished the opportunity to decide their own freedom.

Caption: District of Columbia. Company E, 4th U.S. Colored Infantry, at Fort Lincoln. Library of Congress.

The two Civil War veterans in this scene have a chance encounter on the street where they enlisted. As in Scene 1, these veterans face the unique challenges of shedding and gaining new identities after the war, especially new names.

The two Civil War veterans in this scene have a chance encounter on the street where they enlisted. As in Scene 1, these veterans face the unique challenges of shedding and gaining new identities after the war, especially new names.

Caption: Civil War Soldier (believed to be Sergeant Samuel Smith) and family, c1865, Library of Congress.

John Bolts

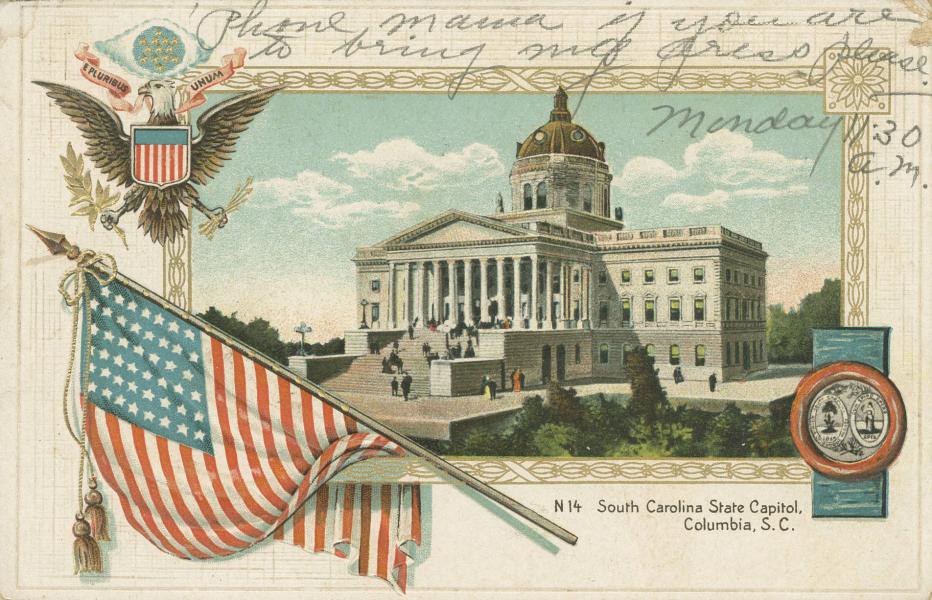

In 1861, John Bolts was born in Plantersville, SC, just as the Civil War began. His parents had been enslaved workers on the Pipe Down Plantation on Sandy Island, but they moved to Plantersville to give John a better education. At the age of 18, he left for Benedict College in Columbia to receive his teaching certification, and he returned to teach in three to four-month stints on Sandy Island and Plantersville.

In 1861, John Bolts was born in Plantersville, SC, just as the Civil War began. His parents had been enslaved workers on the Pipe Down Plantation on Sandy Island, but they moved to Plantersville to give John a better education. At the age of 18, he left for Benedict College in Columbia to receive his teaching certification, and he returned to teach in three to four-month stints on Sandy Island and Plantersville.

This narrative features a fictional Sandy Island girl named Sarah, who was taught by John Bolts. Like many schools of the time, classes were held inside of one of the community’s churches. Sarah’s school was in Butler AME Chapel near where the Sandy Island School stands today.

Caption: Children on Sandy Island, photographed by Bayard Wooten, Brookgreen Gardens Collection.

When Bolts began teaching, many of Georgetown’s political representatives, such as the famous US Congressman Joseph Rainey, were Black. But Jim Crow laws gradually eliminated Black representation through policies and violent acts against Black voters. Despite seeing these changes, Bolts was elected twice to the South Carolina congress. In 1898, he was one of seven black men. In 1900, his second term, he was the only one. He would be the last black man to serve in the South Carolina Congress until 1963.

When Bolts began teaching, many of Georgetown’s political representatives, such as the famous US Congressman Joseph Rainey, were Black. But Jim Crow laws gradually eliminated Black representation through policies and violent acts against Black voters. Despite seeing these changes, Bolts was elected twice to the South Carolina congress. In 1898, he was one of seven black men. In 1900, his second term, he was the only one. He would be the last black man to serve in the South Carolina Congress until 1963.

Caption: John Bolts, c1898, Georgetown Dreamkeepers Collection.

While John Bolts was getting his teaching certification at Benedict College in Columbia, South Carolina, he likely faced what many college students face: home sickness. He was more than a day's journey away from his family and community, approaching the end of his studies, when he received an invitation from Philip Washington, the founder of the freedman community on Sandy Island, calling him home.

While John Bolts was getting his teaching certification at Benedict College in Columbia, South Carolina, he likely faced what many college students face: home sickness. He was more than a day's journey away from his family and community, approaching the end of his studies, when he received an invitation from Philip Washington, the founder of the freedman community on Sandy Island, calling him home.

Caption: John Bolts, c1898, Georgetown Dreamkeepers Collection.

Lillie Knox

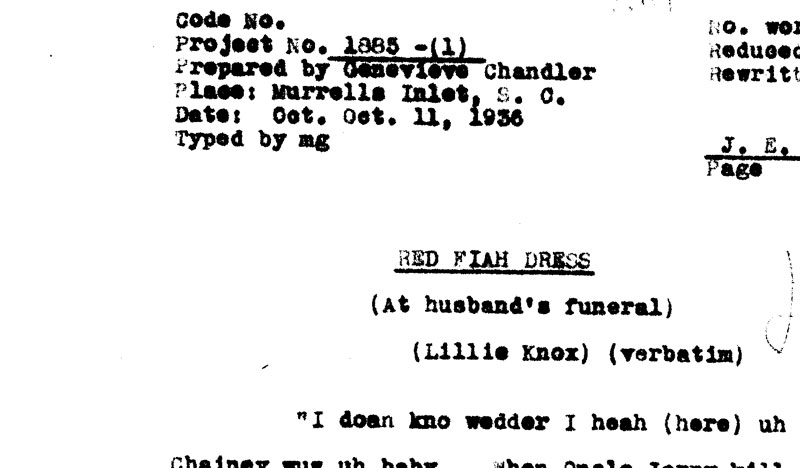

Lillie Knox was a collaborator and housekeeper for Genevieve Chandler, the first curator of Brookgreen and a local historian, during the 1929s through the 1940s. Chandler and Knox wrote many stories on the unique Gullah culture of Murrell's Inlet, some of which are now housed at the Library of Congress. Excerpts of recordings and contemporary reimagines of these are included in this narrative.

Lillie Knox was a collaborator and housekeeper for Genevieve Chandler, the first curator of Brookgreen and a local historian, during the 1929s through the 1940s. Chandler and Knox wrote many stories on the unique Gullah culture of Murrell's Inlet, some of which are now housed at the Library of Congress. Excerpts of recordings and contemporary reimagines of these are included in this narrative.

Caption: First page of Red Fiah Dress, by Lillie Knox and Geneveieve Chandler, 1936, Library of Congress.

Lillie Knox was a member of Heaven's Gate Church, just to the north of Brookgreen Gardens, which still stands to this day. Like many Gullah churches, Heavens Gate celebrated Watch Night, a New Year's Eve service that celebrated the adoption of the Emancipation Proclamation in 1863. In this narrative from the 1930s, we hear from Knox herself on the meaning of faith for her community.

Lillie Knox was a member of Heaven's Gate Church, just to the north of Brookgreen Gardens, which still stands to this day. Like many Gullah churches, Heavens Gate celebrated Watch Night, a New Year's Eve service that celebrated the adoption of the Emancipation Proclamation in 1863. In this narrative from the 1930s, we hear from Knox herself on the meaning of faith for her community.

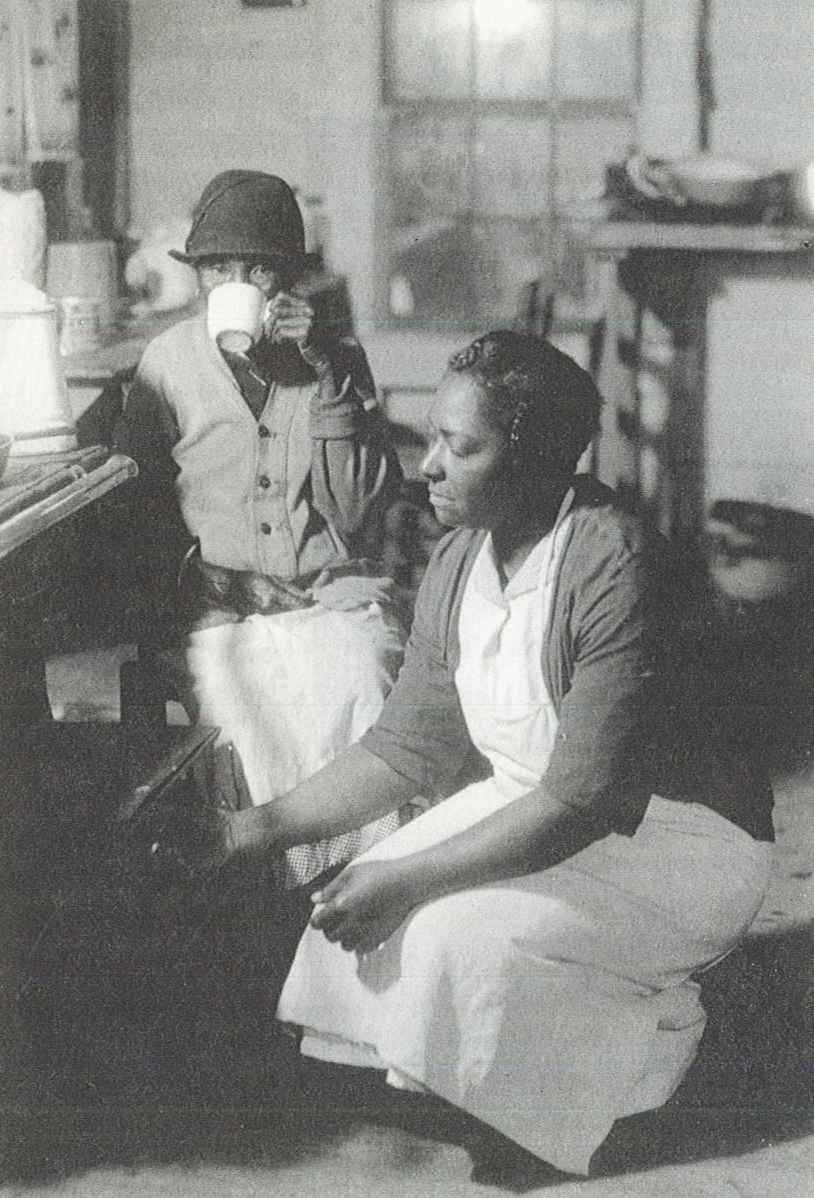

Caption: Lillie Knox and Hagar Brown, photographed by Bayard Wooten, North Carolina Collection, University of North Carolina Library at Chapel Hill.

At the height of the Great Depression in the 1930s, President Roosevelt authorized a new organization called the Workers Progress Administration to document the diverse stories of this country. John Lomax, armed with a wax cylinder recorder, traveled between Arkansas and North Carolina to document folk songs. He learned about the Gullah communities of Murrells Inlet and Georgetown from local community leader Geneveieve Chandler. When Lomax came to town, he recorded Lillie Knox’s beautiful soprano voice singing some of the spirituals popular in her church.

At the height of the Great Depression in the 1930s, President Roosevelt authorized a new organization called the Workers Progress Administration to document the diverse stories of this country. John Lomax, armed with a wax cylinder recorder, traveled between Arkansas and North Carolina to document folk songs. He learned about the Gullah communities of Murrells Inlet and Georgetown from local community leader Geneveieve Chandler. When Lomax came to town, he recorded Lillie Knox’s beautiful soprano voice singing some of the spirituals popular in her church.

Caption: John Lomax in Alabama, 1940, Lomax Collection, Library of Congress.

Ruby Forsythe

Scene 1:

Ruby Forsythe, or Miss Ruby, was the principal teacher at Baskervill, where Holy Cross Faith Memorial Episcopal Church stands today. Miss Ruby was born in 1905, and came to the area from Charleston to teach alongside her husband, Reverend William Fosythe, in 1938. While it took her ten years to move from Charleston to Pawleys Island, it didn't take her long to find her purpose.

Ruby Forsythe, or Miss Ruby, was the principal teacher at Baskervill, where Holy Cross Faith Memorial Episcopal Church stands today. Miss Ruby was born in 1905, and came to the area from Charleston to teach alongside her husband, Reverend William Fosythe, in 1938. While it took her ten years to move from Charleston to Pawleys Island, it didn't take her long to find her purpose.

Caption: Ruby Forsythe, c1930. Georgetown County Rice Museum.

For over forty years, Ruby Forsythe taught children in the area and became actively involved in the NAACP. While most community members knew Miss Ruby for her educational outreach, she occasionally commented on the area's changes, revealing her commitment to the larger Civil Rights movement.

For over forty years, Ruby Forsythe taught children in the area and became actively involved in the NAACP. While most community members knew Miss Ruby for her educational outreach, she occasionally commented on the area's changes, revealing her commitment to the larger Civil Rights movement.

Caption: Miss Ruby Forsythe, photographed by Cecelia Knonyn, The Sun News.

Ruby Forsythe taught hundreds of students from the 1930s to the 1980s. Henry Green, remembers his time in Miss Ruby's classroom and the importance of her lessons and discipline. This account is a fictionalized representation based on the recorded testimonies and scholarship on the importance of Miss Ruby and other black women educators to the Civil Rights Movement.

Ruby Forsythe taught hundreds of students from the 1930s to the 1980s. Henry Green, remembers his time in Miss Ruby's classroom and the importance of her lessons and discipline. This account is a fictionalized representation based on the recorded testimonies and scholarship on the importance of Miss Ruby and other black women educators to the Civil Rights Movement.

Caption: Miss Ruby, c1980, and children. Miss Ruby’s Kids.

Veronica Gerald

Veronica Gerald was raised just to the north in Conway, South Carolina, and is an accomplished storyteller and scholar of Gullah traditions. Gerald reflects the importance to her Gullah community of knowing your roots and family to help preserve and protect these traditions.

Veronica Gerald was raised just to the north in Conway, South Carolina, and is an accomplished storyteller and scholar of Gullah traditions. Gerald reflects the importance to her Gullah community of knowing your roots and family to help preserve and protect these traditions.

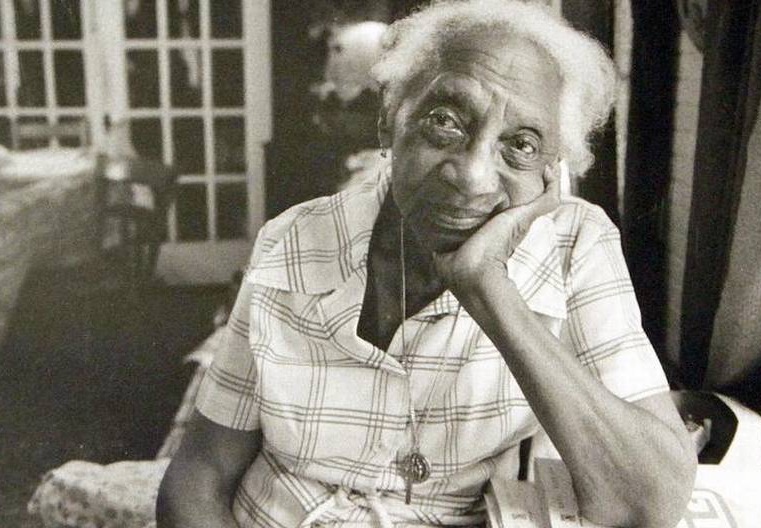

Gerald attended Whittemore High School in Conway, and became an accomplished professor, storyteller. She served on the Gullah Geechee Cultural Heritage Corridor Commission when it was formed by the US Congress in 2006. She is a professor emeritus at Coastal Carolina University.

Caption: Veronica Gerald, South Carolina ETV.

Veronica Gerald, though she was raised in Conway, has deep roots at Brookgreen Gardens. In this narrative, Gerald remembers her mother, aunt, and grandmother, who all had ties back to Murrells Inlet and the lands that are now known as Brookgreen Gardens.

Veronica Gerald, though she was raised in Conway, has deep roots at Brookgreen Gardens. In this narrative, Gerald remembers her mother, aunt, and grandmother, who all had ties back to Murrells Inlet and the lands that are now known as Brookgreen Gardens.

If you are interested in hearing from other families who have ties to Brookgreen, visit the Gullah Geechee Gaardin exhibit in the Lowcountry Center courtyard. Gerald also discusses her family ties in her publications and cookbook.

Caption: Veronica Gerald, Coastal Carolina University.

Veronica Gerald, who attended the University of Maryland, became an accomplished professor, storyteller, and served on the Gullah Geechee Cultural Heritage Corridor Commission when it was formed by the US Congress in 2006. Gerald grew up somewhat ashamed of her Gullah identity. Not many people born within the federally-designated Gullah Geechee Cultural Heritage Corridor claim their identity as Gullah Geechee, in part due to the negative stereotypes about the Gullah culture and language. But as Gullah becomes recognized as a unique and important language and culture, more individuals are reclaiming the Gullah Geechee identity, and they are helping reconnect unique traditions of the Lowcountry back to their African roots.

Veronica Gerald, who attended the University of Maryland, became an accomplished professor, storyteller, and served on the Gullah Geechee Cultural Heritage Corridor Commission when it was formed by the US Congress in 2006. Gerald grew up somewhat ashamed of her Gullah identity. Not many people born within the federally-designated Gullah Geechee Cultural Heritage Corridor claim their identity as Gullah Geechee, in part due to the negative stereotypes about the Gullah culture and language. But as Gullah becomes recognized as a unique and important language and culture, more individuals are reclaiming the Gullah Geechee identity, and they are helping reconnect unique traditions of the Lowcountry back to their African roots.

Caption: Veronica Gerald, Coastal Carolina University